MHDC: Why We Do What We Do

Our History

1904

Our Roots

At the time a part of Warrensville Township, this photograph of Lee Road in 1904, depicts the rural nature of the area to eventually become Miles Heights Village and ultimately Cleveland's Lee-Seville neighborhood. (Cleveland Public Library Photo Collection).

1917

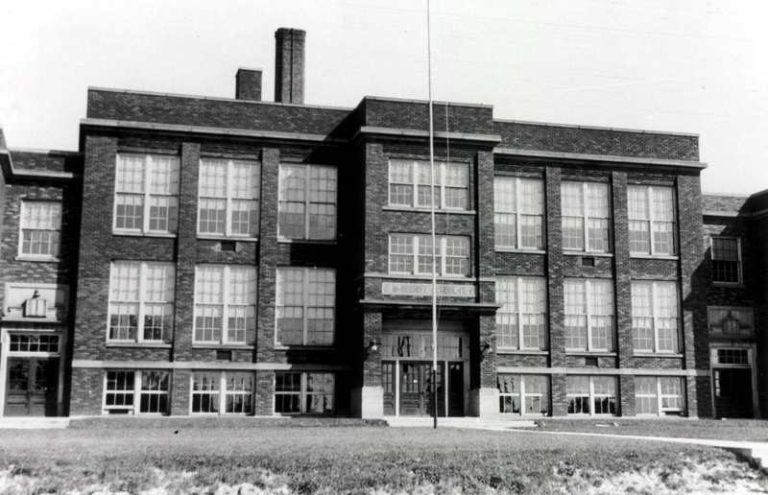

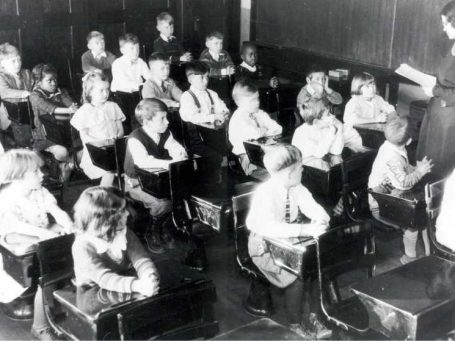

Beehive School Opens

Beehive School was established in 1917 in the area that was known as Miles Heights. It would later become the Miles Heights Village Elementary and Secondary Schools when the area incorporated in 1927. The school was nicknamed "Beehive" because of a nearby resident who harvested honey from bees. Black students were welcomed into classrooms, a testament to both Ohio's heritage as a safe haven for African Americans, as well as to Miles Heights' existence as an integrated community.

1920

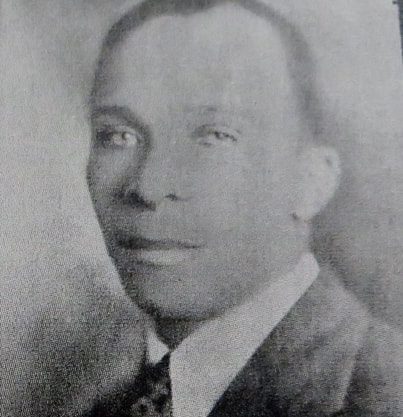

Herbert S. Chauncey

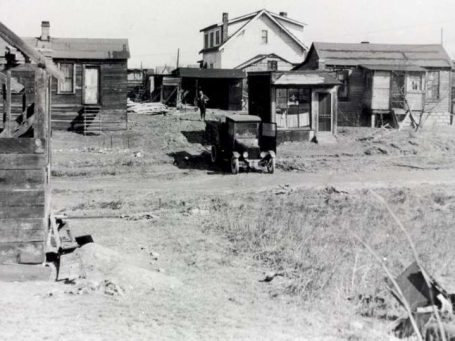

Prior to the 1920s the area now known as Lee-Seville—then a segment of Warrensville Township-- was largely unsettled. This began to change in 1920 when the People’s Realty Co., founded by African American businessman Herbert S. Chauncey, purchased about 100 lots in the already subdivided Bella Villa allotment, just west of the intersection of Lee and Seville rds. The Great Migration was bringing Black southern migrants to the city and numerous families were looking to leave the overly crowded Central neighborhood. Chauncey believed that black families would buy lots in Bella Villa and then save to build their houses, much like others had already done in the Mt. Pleasant area.

About 20 houses already existed in Bella Villa when Chauncy began selling lots in 1921. In 1925 the area’s first church—Canaan Missionary Baptist—was erected, and by 1927 the People’s Realty Co. was reputed to be “the largest realty organization managed by colored people in the city of Cleveland.” That same year, the area was incorporated into the new village of Miles Hts.

1927

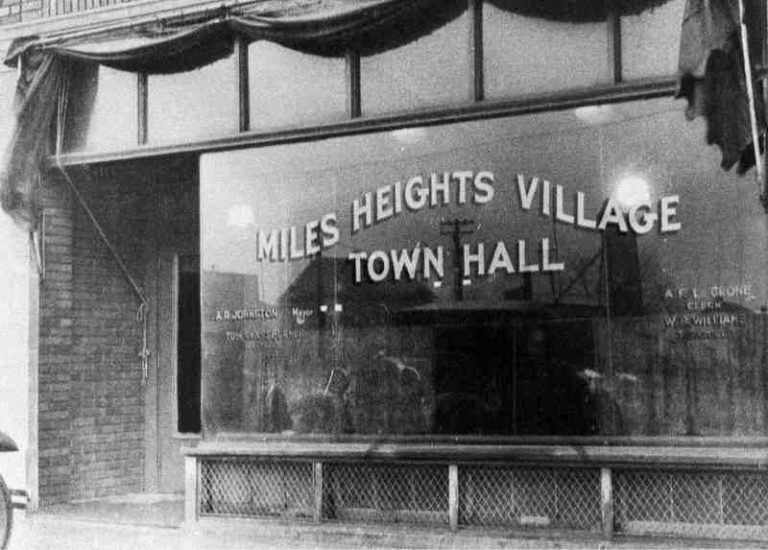

Miles Heights Village Incorporated

Miles Heights Village existed as a suburb of Cleveland between 1927 and 1932. At the time, the village was bounded by Cleveland to the west, Shaker Heights to the north, Warrensville Heights to the east, and Garfield Heights to the south. The center was located at the intersection of Lee and Miles Roads in what is today the Lee-Miles neighborhood in the southeast corner of Cleveland. During its brief history, Miles Heights was one of only a few outlying enclaves where Black Americans lived, as most were confined to the Central neighborhood of Cleveland at that time. Miles Heights counted roughly 500 Blacks alongside 1,000 Whites, mostly European immigrants. Although largely segregated, race relations were remarkably amicable. The Village even had an interracial police force.

1929

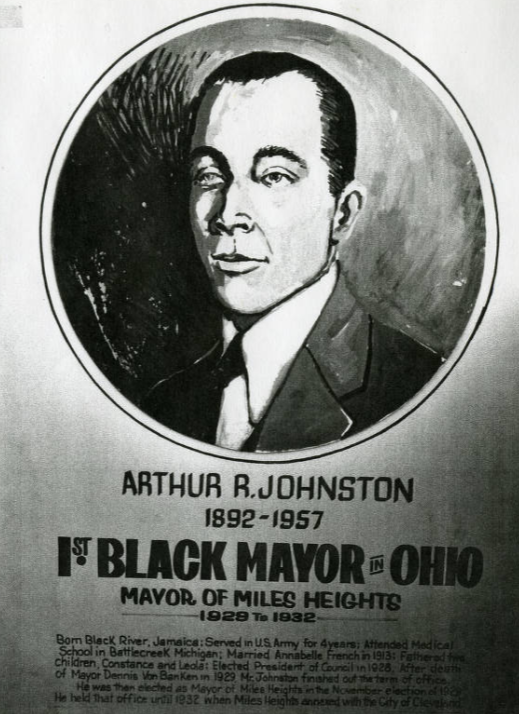

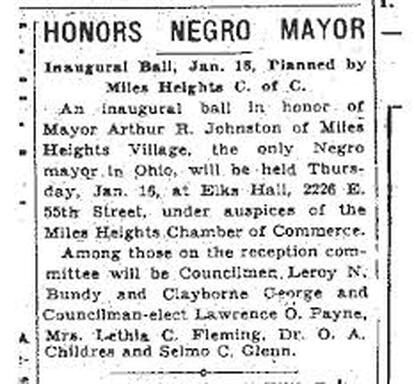

Mayor Arthur R. Johnston

Carl B. Stokes is widely known as the first African American mayor of a major U.S. city. Yet, Stokes, elected to office in 1967, was neither the first Black mayor in Ohio nor even in the Cleveland area. Thirty-eight years earlier, a small community, now inside Cleveland city limits, elected a Jamaican immigrant to its highest office.

After Miles Heights Mayor Dennis H. Von Benken died in office in late 1928, he was succeeded by the incumbent president of the Miles Heights Village Council. Arthur R. Johnston, became the first Black mayor in Ohio at the age of 35. In the election held in fall 1929, Johnston was elected to serve a full two-year term, which was no small feat at that time in a majority-white community.

Mayor Johnston was an Army veteran of World War I, and was also a member of Antioch Baptist Church. After Miles Heights was annexed, Johnston was, for a time, Director of Purchases for the City of Cleveland. From 1938 until he retired in 1954, he was an auditor in the Ohio Department of Taxation.

Johnston continued to work as a sewer foreman for Cuyahoga County during his tenure as village mayor, which stirred considerable controversy.

1932

Miles Heights Village Annexed

Amid fiscal challenges and allegations of corruption, Cuyahoga County Commissioners voted to dissolve Miles Hts. and annex it to Cleveland in December 1931. In 1932 a majority of villagers approved. In a last ditch effort, a number of Miles Heights officials blockaded themselves inside their town hall and were prepared to shoot it out to prevent annexation. Fortunately, serious violence was avoided, and Miles Heights Village officially became a part of Cleveland on March 30, 1932, making what are now the Lee-Seville and Lee-Miles SPAs.

1932-1940

Blacks Prosper, Redlining Comes

By 1930, 135 black families lived in the Bella Villa enclave—roughly 95% of the total population. Ninety percent owned their homes. A grocery store, delicatessen, another church (Original Church of God) and even a “Sportsmen’s Club” were in operation by the end of the 1940s.

White and Black residents coexisted in reasonable harmony in early Miles Hts., but by the late 1930s more racist policies descended on Bella Villa. In 1939 the Home Owners Loan Corp. redlined the settlement as a bad investment, calling it a shantytown with a “very detrimental effect on surrounding area property values.”

1944

The Seville Homes

In 1943, citing a severe housing shortage in the Central neighborhood, the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority filed to build the Seville Homes as “temporary war housing” for Black foundry workers arriving from the South, on 49 acres at the intersection of Seville Rd. and E. 153rd St. Objections from residents of Maple Hts. and Garfield Hts. delayed construction until 1944. Designed by Abram Garfield, the project ultimately comprised 2,000 residents in more than 100 low-rise buildings.

In the late 1940s a group called the Miles Heights Progressive League launched a campaign demanding sewers, paved roads, sidewalks and door-to-door mail service. The city responded by instituting mail delivery, repairing streets, installing some sidewalks, upgrading streetlights and initiating sewer construction. However, full water and sewer service was not completed until 1954. By 1950 3,400 African Americans lived in Lee-Seville.

1949

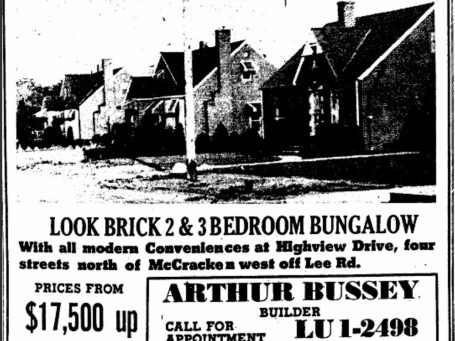

Arthur Bussey Construction

Arthur Bussey was an African American bricklayer and building contractor who moved to Cleveland from Georgia after WWI. He was a housing construction laborer by day and took architectural drafting classes at night, serving as a general contractor in the rebuilding of Emmanuel Baptist Church after a fire destroyed it in 1939. As overcrowding in Cedar Central led many Black residents to seek home purchases in other parts of the city, Bussey took advantage of this opportunity by constructing homes in Lee-Seville.

In July 1947, he purchased a substantial parcel of land in the neighborhood, personally financing the construction of sewers for Myrtle Ave & Highview Drive where, in 1949, he began building several dozen of his nearly 40 mid-century brick homes. Bussey Construction designed the homes to be attractive to higher-income Black buyers. The Myrtle-Highview Historic District is the first historic district in Ward 1 to be named to the National Register of Historic Places.

Origins of Southeast Builders

n 1949, the same year Arthur Bussey built his home on Myrtle Avenue, brick homes began going up a few blocks away. Three men with no formal training in the building trades, all of them recent transplants from the South, made a pact to help build each other’s houses in the Lee- Miles area, on the lots they owned just east of the Seville Homes housing project. Requests to build homes for others led these gentlemen to form the firm Carr & Dillard, although they would later operate under other names as well. One of the most ambitious plans to provide housing for Cleveland’s upwardly mobile African American families ultimately succumbed to the numerous setbacks facing Black-owned construction companies at the time, although it did succeed in erecting at least eighty homes during its brief existence. The story of the firm that after several name changes finished as Southeast Builders was a heartfelt one that received considerable attention in the Call & Post in the early 1950s, due to the circumstances in which its founders met, and because its early activities seemed to embody a “can do” attitude of relying on the community’s own resources to find creative solutions to the problems African Americans faced in acquiring high-quality new homes at the time.

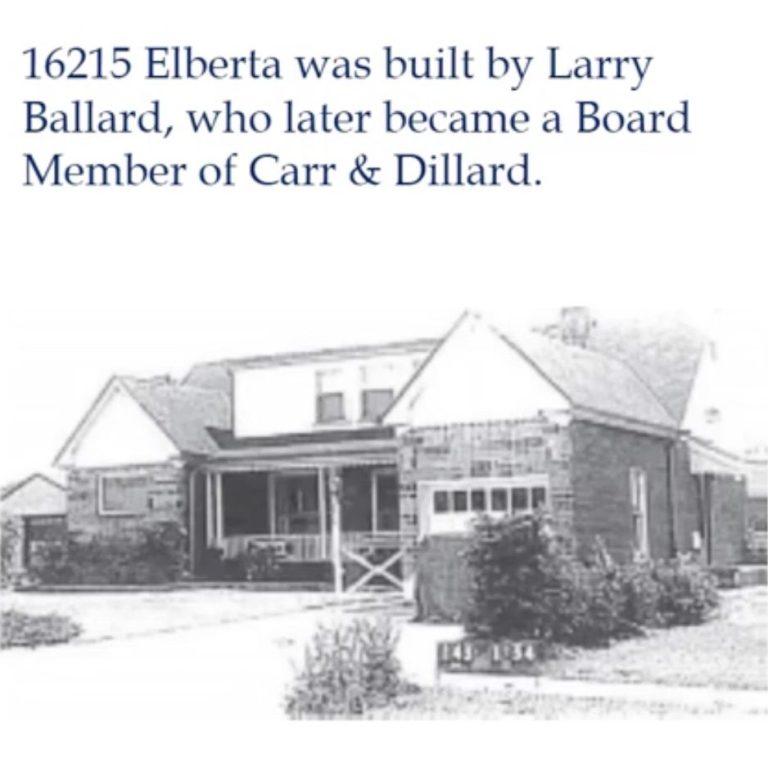

John T. Thomas, was a coal mine operator from Birmingham, Alabama, John B. Harmon hailed from Atlanta, Georgia, where “he had been a house-man-chauffeur-butler but was known far and wide in North Georgia for his unique ability at cooking.” Finally, Leslie Ephraim was a former schoolteacher from Camden, Alabama who migrated to Cleveland around 1942. The three men together first built Ephraim’s house at 4666 East 162nd Street, completing it in just three months. Carrying through on their agreement, they then turned to work on Thomas’s house at 16221 Bryce Avenue, and Harmon’s at 4656 East 162nd Street. The efforts of Thomas, Harmon, and Ephraim attracted the notice of two of their neighbors, Leroy Ballard and his younger brother Brunson, who offered to help them complete the remaining two houses.

Leroy, who had some carpentry experience, had just completed building his own home at 16215 Elberta Avenue. The Ballard brothers were from Columbia County, Arkansas, where their father had owned his own farm. For two years Leroy attended the historically Black Philander Smith College in Little Rock, then taught mathematics before relocating to Cleveland in 1932. In 1940, he lived on East 142nd St. in Mt. Pleasant, working as a junior clerk in Cleveland City Hall. In 1942 he worked as a conductor with the Cleveland Transit System. The Ballard brothers would ultimately build 28 homes in the Lee-Seville neighborhood, including one for each of Leroy’s three children.

1951

Zoning Controversies Begin

By 1950 3,400 African Americans lived in Lee-Seville. Attempts to obstruct Black settlement in the neighborhood continued. In 1951 a zoning change from residential to industrial was approved for a parcel of land at Lee and Seville rds. The underlying purpose of this zoning change was to make less land available for black residents and to sabotage their chances of getting favorable FHA-insured loans. Despite a citywide campaign organized by the NAACP, the change went through and the Electric Controller Co. opened for business. Its owners quickly reneged on their promise to hire black workers.

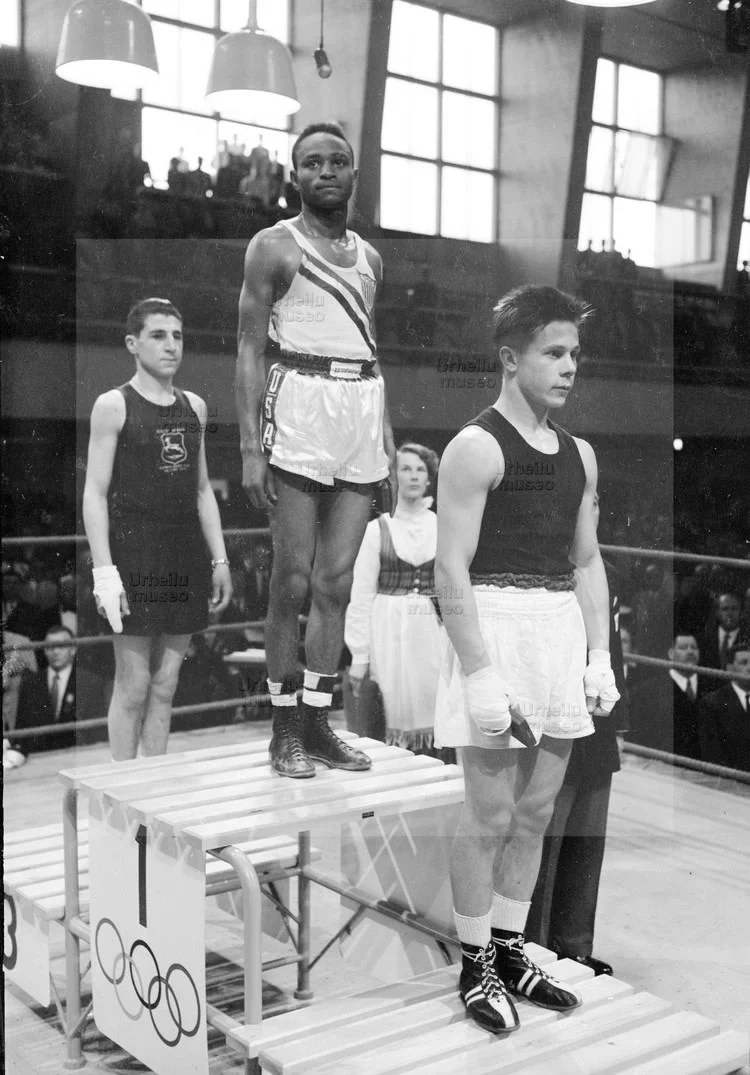

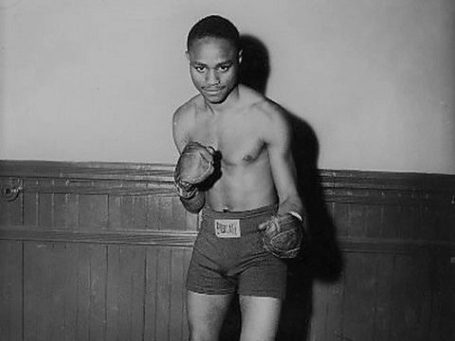

1952

Nate Brooks: Olympic Gold

Greater Cleveland Sports Hall of Fame Member Nathan "Nate" Eugene Brooks boxed his way to gold in the Flyweight Division of the 1952 Helsinki, Finland Summer Games as a member of the exceptional U.S. Olympic Boxing Team. Brooks' road to Olympic Gold began in Cleveland's southeast corner known as Miles Heights Village, one of the few historical suburbs where African Americans lived alongside European immigrants. Born the 8th of 11 children to Frank and Mary Brooks on August 8, 1933, in Cleveland, Ohio, Nate was a bright student and fierce competitor at a young age, as his father and first trainer had a boxing ring set up in their backyard.

Miles Heights Village: The Making of Cleveland's Black Suburb

Video coutesy of Ideastream Public Media, the home of Northeast Ohio’s member-supported public broadcasting stations WVIZ, WKSU and WCLV, your source for trustworthy local journalism, inspiring stories and quality entertainment.

Chapter 1: The Lee-Seville Enclave In Old Miles Heights

Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS) chronicles the life and times of Cleveland, Ohio's Black home builders and their contribution to the foundations of the city’s southeastern region, currently known as The Lee-Seville neighborhood.

Chapter 2: Black Builders Fulfill the Dream South of Miles

Narrated by CRS Marketing & Events Specialist Stephanie Phelps, this video provides a comprehensive summary of Chapter 2: Black Builder-Entrepreneurs Fulfill the Dream South of Miles from The Making of Cleveland's Black Suburb in the City: Lee-Seville & Lee-Harvard.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.